752

Views & Citations10

Likes & Shares

Gender Based Violence (GBV) is any act ‘that results in, or is likely to

result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering’ that is

directed against a person because of their biological sex, gender identity or

perceived adherence to socially defined norms of masculinity and femininity.

GBV includes intimate partner violence and can be physical, sexual, emotional,

economic or structural where that violence targets someone because of their

gender or non-compliance with gender norms. The aim of the guidelines is to

provide an adequate and integrated intervention in the treatment of the

physical and psychological consequences that in particular male violence produces

on women's health.

Keywords: Gender based

violence, Woman health

INTRODUCTION

Gender Based Violence (GBV)

is any act ‘that results in or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or

psychological harm or suffering’ that is directed against a person because of

their biological sex, gender identity or perceived adherence to socially

defined norms of masculinity and femininity. GBV includes intimate partner

violence and can be physical, sexual, emotional, economic or structural where

that violence targets someone because of their gender or non-compliance with gender

norms. It can be experienced by women and girls, men and boys, and transgender

and intersex people of all ages and has direct consequences on health, social,

financial and other aspects of their lives [1].

GBV takes on many forms and

can occur throughout the lifecycle, from the prenatal phase through childhood

and adolescence, the reproductive years and old age [2].

Types of GBV

The WHO divided GBV in two

groups:

·

Gender-based violence:

o

Rape by strangers

o

Female genital mutilation

o

Sexual harassment in the workplace

o

Selective malnutrition of girls

·

Domestic/Family violence:

o

Child abuse

o

Elder abuse

Intimate partner violence

and sexual abuse of women and girls in the family are overlapped in these two

groups [3].

Epidemiologies

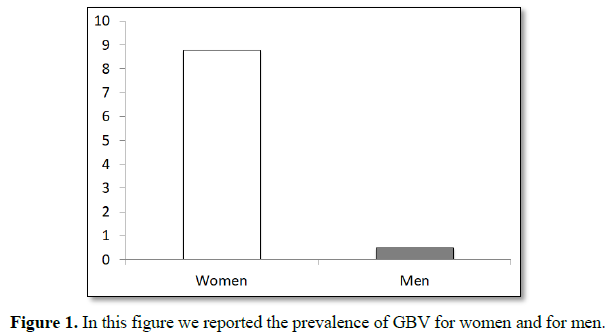

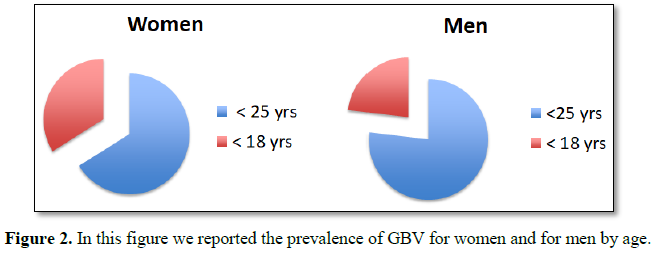

The lifetime prevalence of

rape by an intimate partner was an estimated 8.8% for women and an estimated

0.5% for men (Figure 1). An estimated 15.8% of women and 9.5% of men

experienced other forms of sexual violence by an intimate partner during their

lifetimes. Severe physical violence by an intimate partner was experienced by

an estimated 22.3% of women and 14.0% of men during their lifetimes. Among

female victims of completed rape, an estimated 78.7% were first raped before

age 25 years, with 40.4% experiencing rape before age 18 years. Among male

victims who were made to penetrate a perpetrator, an estimated 71.0% were

victimized before age 25 years and an estimated 21.3% were victimized before

age 18 years (Figure 2) [4].

In one cross sectional

study, 11.7% of women visiting a variety of American emergency departments were

there because of acute injury or stress related to domestic violence. The

lifetime prevalence rate for domestic violence of 54.2% in women attending Emergency

Departments (ED) [5]

In a study population 12.6%

of men attending emergency departments were victims of domestic violence by a

current or former female intimate partner [6]. These data demonstrate how

important GBV is to an emergency physician.

Risk factors

Individual factors:

·

Young age

·

Heavy drinking

·

Depression

·

Personality disorders

·

Low academic achievement

·

Low income

·

Witnessing or experiencing violence as a child

Relationship factors:

·

Marital conflict

·

Marital instability

·

Male dominance in the family

·

Economic stress

·

Poor family functioning

Community factors:

·

Weak community sanctions against domestic violence

·

Poverty

·

Low social capital

Social factors:

·

Traditional gender norms

·

Social norms supportive of violence [7-10]

Health consequences

GBV has both physical and

psychological consequences.

Physical:

· Headaches

·

Back pain and other musculoskeletal pain

·

Chest pain

·

Gynecological disorders including menstrual disorders, pelvic pain and

dyspareunia

·

Sexually transmitted diseases, including HIV/AIDS

·

Gastrointestinal disorders

·

Urinary tract infection

·

Acute respiratory infection

Psychological:

·

Anxiety

·

Substance use

·

Tobacco use

·

Family and social problems

·

Depression [11]

MANAGEMENT IN ED

An American study identified that

emergency department use was common in the two years before murder by a

partner. In USA, a spouse or intimate partner perpetrated 33.6% of female

homicides, while less than 8% of murders of men were perpetrated by a spouse or

intimate partner [5].

a. How to detect GBV?

It seems that history taking and

clinical examination is unsatisfactory for diagnosing domestic violence. While

the evidence does not support screening for domestic violence, it is still

important that emergency physicians know how to create the opportunity of a

patient disclosing domestic violence, so that self-reported victims of domestic

violence can be offered help. Ideally all consultations should take place in a

private room with, initially, only the patient and the doctor. Simple, direct,

non-judgmental questions are the best way to inquire about domestic violence if

this is felt appropriate. The partner violence scale (PVS) consists of three

questions (Have you been hit, kicked, punched or otherwise hurt by someone

within the past year? Do you feel safe in your current relationship now? Is

there a partner from a previous relationship who is making you feel unsafe

now?) That have been compared with both the index spouse abuse (ISA) and the

conflict tactics scale (CTS), two validated measures of domestic violence. The

first question proved to be nearly as useful as all three questions at

identifying victims. The sensitivity of the PVS compared with the ISA was 65%;

specificity was 80% with a positive predictive value of 51% [5].

b. Management of an identified victim

As always the priority is to

treat the physical injury. It should be explained to the victim that domestic

violence is unacceptable and against the law. Police contact should be offered

while in the comparative safety of the emergency department. It is much easier

to contact the police from the emergency department than a household that is

shared with the perpetrator [5].

SPECIAL CASES

Elder abuse

The definition developed by

Action on Elder Abuse in the United Kingdom and adopted by the International

Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse states that: “Elder abuse is a single

or repeated act or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any

relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or

distress to an older person.” Such abuse is generally divided into the

following categories:

·

Physical abuse – the infliction of pain or injury,

physical coercion or physical or drug induced restraint.

·

Psychological or emotional abuse – the infliction of

mental anguish.

·

Financial or material abuse – the illegal or improper

exploitation or use of funds or resources of the older person.

·

Sexual abuse – non-consensual sexual contact of any kind

with the older person.

·

Neglect – the refusal or failure to fulfil a caregiving

obligation. This may or may not involve a conscious and intentional attempt to

inflict physical or emotional distress on the older person.

The rate of abuse is 4-6% among

older people if physical, psychological and financial abuse and neglect are all

included. For older people, the consequences of abuse can be especially

serious. Older people are physically weaker and more vulnerable than younger

adults, their bones are more brittle and convalescence takes longer. Even a

relatively minor injury can cause serious and permanent damage. Many older

people survive on limited incomes, so that the loss of even a small sum of

money can have a significant impact. They may be isolated, lonely or troubled

by illness, in which case they are more vulnerable as targets for fraudulent

schemes.

The medical profession has played

a leading role in raising public concern about elder abuse. While it may be

thought that doctors are best placed to notice cases of abuse – partly because

of the trust that most elderly people have in them – many doctors do not

diagnose abuse because it is not part of their formal or professional training

and hence does not feature in their list of differential diagnoses. Most

emergency departments do not use protocols to detect and deal with elder abuse,

and rarely attempt to address the mental health or behavioral signs of elder

abuse, such as depression, attempted suicide, or drug or alcohol abuse [7].

There should be an

investigation of a patient’s condition for possible abuse if a doctor or other

health care worker notices any of the following signs:

·

Delays between injuries or illness and seeking medical attention;

·

Implausible or vague explanations for injuries or ill-health, from either

the patient or his or her caregiver;

·

Differing case histories from the patient and the caregiver;

·

Frequent visits to emergency departments because a chronic condition has

worsened, despite a care plan and resources to deal with this in the home;

·

Functionally impaired older patients who arrive without their main

caregivers;

·

Laboratory findings that are inconsistent with the history provided.

When conducting an

examination the doctor or health care worker should:

·

Interview the patient alone, asking directly about possible physical

violence, restraints or neglect;

·

Interview the suspected abuser alone;

·

Pay close attention to the relationship between and the behavior of, the

patient and his or her suspected abuser;

·

conduct a comprehensive geriatric assessment of the patient, including

medical, functional, cognitive and social factors;

·

Document the patient’s social networks, both formal and informal [12].

Child abuse

The WHO Consultation

on Child Abuse Prevention drafted the following definition [8]: “Child abuse or

maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment,

sexual abuse neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other

exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child’s health,

survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of

responsibility, trust or power” [13].

There are four types

of child maltreatment by caregivers, namely:

·

Physical abuse;

·

Sexual abuse;

·

Emotional abuse;

·

Neglect

According to the

World Health Organization, there were an estimated 57 000 deaths attributed to

homicide among children under 15 years of age in 2000. Global estimates of

child homicide suggest that infants and very young children are at greatest

risk, with rates for the 0-4 year old age group more than double those of 5-14

year olds. World for children under 5 years of age living in high-income

countries, the rate of homicide is 2.2 per 100 000 for boys and 1.8 per 100 000

for girls. In low- to middle-income countries the rates are 2-3 times higher –

6.1 per 100 000 for boys and 5.1 per 100 000 for girls [7]. Ill health caused

by child abuse forms a significant portion of the global burden of disease.

Importantly, there is now evidence that major adult forms of illness –

including ischemic heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease, irritable bowel

syndrome and fibromyalgia – are related to experiences of abuse during

childhood. The apparent mechanism to explain these results is the adoption of

behavioral risk factors such as smoking, alcohol abuse, poor diet and lack of

exercise. Research has also highlighted important direct acute and long-term

consequences [14,15].

Other survivors have

serious psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, substance abuse,

aggression, shame or cognitive impairments. Finally, some children meet the

full criteria for psychiatric illnesses that include post-traumatic stress

disorder, major depression, anxiety disorders and sleep disorders [16]. Studies

in various countries have highlighted the need for the continuing education of

health care professionals on the detection and reporting of early signs and

symptoms of child abuse and neglect [17]. In the United States the American

Medical Association and the American Academy of Pediatrics have produced

diagnostic and treatment guidelines for child maltreatment and sexual abuse

[18].

Domestic violence among male patients

In a study population 12.6% of men attending emergency departments were victims of domestic violence by a current or former female intimate partner. In 1978, Steinmetz described “the battered husband syndrome.” She suggested that violence committed by women against their male partners had been largely ignored for several reasons. First, there is a stigma associated with being a man beaten by a woman. Therefore, men are unlikely to admit that they have been assaulted by their partners. Second, injuries inflicted by women on men tend to be less severe and presumably less visible. Finally, there has been little research or media attention on the subject. The most common types of abuse involved unarmed physical assaults and throwing of objects. The use of weapons was less common. Few victims sought help of any type, whether it is legal action, medical attention or counseling [6].

ITALIAN LEGISLATION ABOUT GBV

The first significant

legislative innovation in the field of sexual violence, in Italy, took place

with the approval of the Law of 15 February 1996, n. 66, which began to

consider violence against women as a crime against personal freedom, innovating

the previous legislation, which placed it among the crimes against public

morality and good morals.

With the Law 4 April

2001, n. 154 new measures are introduced aimed at combating cases of violence

within the home with the removal of the violent family member. In the same year

the Laws n. 60 and the Law of 29 March 2001, n. 134 on legal aid for women,

without financial means, raped and/or ill-treated, a fundamental instrument to

defend them and assert their rights, in collaboration with the anti-violence

centers and the courts.

With the Law of 23

April 2009, n. 38 penalties for sexual violence have been exacerbated and the

crime of persecutory acts or stalking is introduced.

Italy has taken a

historic step in the fight against gender violence with the law of 27 June 2013

n. 77, approving the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, drawn up on May

11, 2011. The guidelines outlined by the Convention are in fact the track and

the lighthouse to implement effective measures, at national level, and to

prevent and combat this phenomenon. On October 15, 2013 Law 119/2013 was

approved (in force since October 16, 2013) “Conversion into law, with

amendments, of the decree-law 14 August 2013, n. 93, which contains urgent

provisions on security and to combat gender-based violence”. On 24 November

2017, “the National Guidelines for Aziende Sanitarie and Aziende Ospedaliere on

the issue of relief and social-health assistance to women victims of violence”

were approved.

CONCLUSION

The aim of the

guidelines is to provide an adequate and integrated intervention in the

treatment of the physical and psychological consequences that male violence

produces on women's health. The provision provides, after the nursing triage,

unless it is necessary to assign an emergency code (red or equivalent), that

the woman is recognized a codification of relative urgency (yellow code or

equivalent) to ensure a timely medical examination (time of maximum waiting

time 20 min) and minimize the risk of voluntary repentance or departure.

The guidelines also

provide for the continuous updating of operators and operators, essential for a

good reception, taking charge, risk detection and prevention [19].

1. Policy

and Programme Guidance: HIV and gender-based violence. UN Women Regional Office

for Asia and the Pacific. WHO.

2. Khan

A (2011) Gender-based violence and HIV: A program guide for integrating

gender-based violence prevention and response in PEPFAR programs. Arlington,

VA: USAID’s AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources, AIDSTAR-One, Task

Order 1.

3. Ellsberg

M, Heise L (2005) Researching violence against women: A practical guide for

researchers and activists. Washington DC, United States: World Health

Organization, PATH.

4. Breding

MJ (2014) Prevalence and characteristics of sexual violence, stalking and

intimate partner violence victimization — National Intimate Partner and Sexual

Violence Survey, United States, 2011. MMWR Surveill Summ 63: 1-18.

5. Boyle

A, Robinson S, Atkinson P (2004) Domestic violence in emergency medicine

patients. Emerg Med J 21: 9-13.

6. Mechem

CC, Shofer FS, Reinhard SS (1999) History of domestic violence among male

patients presenting to an urban emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 6.

7. Krug

E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA (2002) World report on violence and health. Geneva,

World Health Organization.

8. McCloskey

LA, Lichter E, Ganz ML (2005) Intimate partner violence and patient screening

across medical specialties. Acad Emerg Med 12: 712.

9. Crandall

ML, Nathens AB, Kernic MA (2004) Predicting future injury among women in

abusive relationships. J Trauma 56: 906.

10. Khalifeh

H, Oram S, Trevillion K (2015) Recent intimate partner violence among people

with chronic mental illness: Findings from a national cross-sectional survey.

Br J Psychiatry 207: 207.

11. Bonomi

AE, Anderson ML, Reid RJ (2009) Medical and psychosocial diagnoses in women

with a history of intimate partner violence. Arch Intern Med 169: 1692-1697.

12. Lachs

MS, Pillemer KA (1995) Abuse and neglect of elderly persons. N Engl J Med 332:

437-443.

13. WHO

(1999) Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention. Geneva, World

Health Organization.

14. Anda

R (1999) Adverse childhood experiences and smoking during adolescence and

adulthood. J Am Med Assoc 282: 1652-1658.

15. Felitti

V (1998) Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of

the leading causes of death in adults. Am J Prev Med 14: 245-258.

16. Fergusson

DM, Horwood MT, Lynskey LJ (1996) Childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric

disorder in young adulthood. II: Psychiatric outcomes of childhood sexual

abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35:

1365-1374.

17. Alpert

EJ (1998) Family violence curricula in US medical schools. Am J Prev Med 14:

273-278.

18. American

Academy of Pediatrics (1999) Guidelines for the evaluation of sexual abuse of

children: Subject review. Pediatrics 103: 186-191.